- The Tesla Model S sedan and Model X SUV going out of production.

- Tesla CEO Elon Musk said that if you want one of these models, "now would be the time to order it."

- The Model S and Model X combined accounted for less than 3% of Tesla's total deliveries in 2025.

The Tesla Model S and Model X aren't long for this world. That's the news from Tesla CEO Elon Musk, who confirmed the demise of these EVs on the company's recent fourth-quarter earnings call.

"It's time to basically bring the Model S and X programs to an end," Musk said. "If you’re interested in buying a Model S and X, now would be the time to order it."

The Model S and Model X are the two oldest vehicles in Tesla's lineup; the Model S was originally launched way back in 2012 and the Model X followed a few years later. Since then, these vehicles have received several over-the-air tech updates, but only minor tweaks to the physical hardware. The last significant milestone came in 2021, when Tesla launched the high-performance Model S Plaid and Model X Plaid. You may remember the Model S Plaid from Edmunds U-Drags where it lost to both of its key rivals, the Lucid Air Sapphire and Porsche Taycan Turbo GT.

Sales of the Model S and Model X have suffered in recent years. Of the 1,636,129 vehicles Tesla delivered in 2025, 97% were the far more popular Model 3 and Model Y, both of which have recently been overhauled.

It's unclear exactly when production of the Model S and Model X will end. Following that, Musk said Tesla's factory in Fremont, California, will be retooled to build Optimus humanoid robots. Neat.

Anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and death. These can be the consequences for vulnerable kids who get addicted to social media, according to more than 1,000 personal injury lawsuits that seek to punish Meta and other platforms for allegedly prioritizing profits while downplaying child safety risks for years.

Social media companies have faced scrutiny before, with congressional hearings forcing CEOs to apologize, but until now, they've never had to convince a jury that they aren't liable for harming kids.

This week, the first high-profile lawsuit—considered a "bellwether" case that could set meaningful precedent in the hundreds of other complaints—goes to trial. That lawsuit documents the case of a 19-year-old, K.G.M, who hopes the jury will agree that Meta and YouTube caused psychological harm by designing features like infinite scroll and autoplay to push her down a path that she alleged triggered depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicidality.

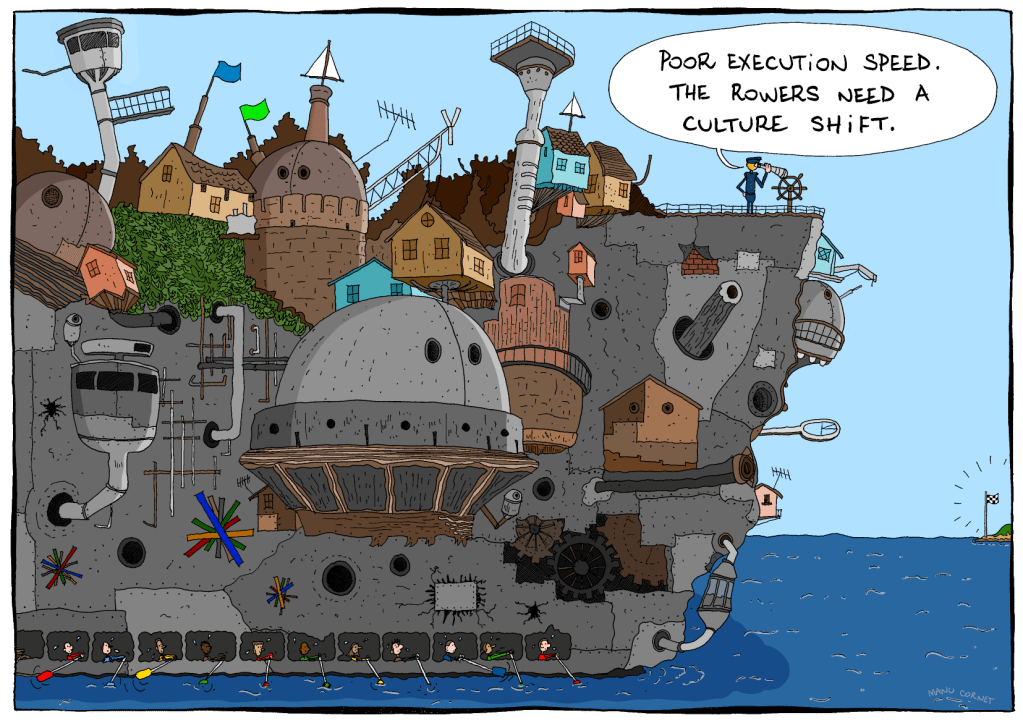

If you’ve ever worked at a larger organization, stop me if you’ve heard (or asked!) any of these questions:

- “Why do we move so slowly as an organization? We need to figure out how to move more quickly.”

- “Why do we work in silos? We need to figure out how to break out of these.”

- “Why do we spend so much of our time in meetings? We need to explicitly set no-meeting days so we can actually get real work done.”

- “Why do we maintain multiple solutions for solving what’s basically the same problem? We should just standardize on one solution instead of duplicating work like this.”

- “Why do we have so many layers of management? We should remove layers and increase span of control.”

- “Why are we constantly re-org’ing? Re-orgs so disruptive.”

(As an aside, my favorite “multiple solutions” example is workflow management systems. I suspect that every senior-level engineer has contributed code to at least one home-grown workflow management system in their career).

The answer to all of these questions is the same: because coordination is expensive. It requires significant effort for a group of people to work together to achieve a task that is too large for them to accomplish individually. And the more people that are involved, the higher that coordination effort grows. This is both “effort” in terms of difficulty (effortful as hard), and in terms of time (engineering effort, as measured in person-hours). This is why you see siloed work and multiple systems that seem to do the same thing. It’s because it requires less effort to work within your organization then to coordinate across organization, the incentive is to do localized work whenever possible, in order to reduce those costs.

Time spent in meetings is one aspect of this cost, which is something people acutely feel, because it deprives them of their individual work time. But the meeting time is still work, it’s just unsatisfying-feeling coordination work. When was the last time you talked about your participation in meetings in your annual performance review? Nobody gets promoted for attending meetings, but we humans need them to coordinate our work, and that’s why they keep happening. As organizations grow, they require more coordination, which means more resources being put into coordination mechanisms, like meetings and middle management. It’s like an organizational law of thermodynamics. It’s why you’ll hear ICs at larger organizations talk about Tanya Reilly’s notion of glue work so much. You’ll hear companies run “One <COMPANY NAME>” campaigns at larger companies as an attempt to improve coordination; I remember the One SendGrid campaign back when I worked there.

Because of the challenges of coordination, there’s a brisk market in coordination tools. Some examples off the top of my head include: Gantt charts, written specifications, Jira, Slack, daily stand-ups, OKRs, kanban boards, Asana, Linear, pull requests, email, Google docs, Zoom, I’m sure you could name dozens more, including some that are no longer with us. (Remember Google Wave?). Heck, both spoken and written language are the ultimately communication ur-tools.

And yet, despite the existence of all of those tools, it’s still hard to coordinate. Remember back in 2002 when Google experimented with eliminating engineering managers? (“That experiment lasted only a few months“). And then in 2015 when Zappos experimented with holacracy? (“Flat on paper, hierarchy in practice.“) I don’t blame them for trying different approaches, but I’m also not surprised that these experiments failed. Human coordination is just fundamentally difficult. There’s no one weird trick that is going to make the problem go away.

I think it’s notable that large companies try different strategies to try to manage ongoing coordination costs. Amazon is famous for using a decentralization strategy, they have historically operated almost like a federation of independent startups, and enforce coordination through software service interfaces, as described in Steve Yegge’s famous internal Google memo. Google, on the other hand, is famous for using an invest-heavily-in-centralized-tooling approach to coordination. But there are other types of coordination that are outside of the scope of these sorts of solutions, such as working on an initiative that involves work from multiple different teams and orgs. I haven’t worked inside of either Amazon or Google, so I don’t know how well things work in practice there, but I bet employees have some great stories!

During incidents, coordination becomes an acute problem, and we humans are pretty good at dealing with acute problems. The organization will explicitly invest in an incident manager on-call rotation to help manage those communication costs. But coordination is also a chronic problem in organizations, and we’re just not as good at dealing with chronic problems. The first step, though, is recognizing the problem. Meetings are real work. That work is frequently done poorly, but that’s an argument for getting better at it. Because that’s important work that needs to get done. Oh, also, those people doing glue work have real value.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Using the concept of FROGs introduced by everyones friend Joe Posnanski, we start our FROG in 1940, with the following 12 Knights of the FROG table, listed by age, the 12 greatest living ballplayers, aged 35+:

- 73 Cy Young

- 66 Honus Wagner

- 66 Nap Lajoie

- 56 Pop Lloyd

- 54 Ty Cobb

- 53 Walter Johnson

- 53 Pete Alexander

- 52 Tris Speaker

- 45 Babe Ruth

- 44 Rogers Hornsby

- 44 Oscar Charleston

- 37 Lou Gehrig

And an honourary FROGhood for the already-departed: Christy Mathewson (1925), age 45

We immediately lose our first FROG in 1941: Lou Gehrig

We introduce in 1942: Lefty Grove, age 41

Walter Johnson will depart in 1946, so we add a new member: Josh Gibson

We will now lose members very quickly in the coming years:

Josh Gibson departs the following year in 1947, and we add Satchel Paige, age 41

Babe Ruth will depart in 1948, and we add Eddie Collins, age 60

Pete Alexander will depart in 1950, and we add Kid Nichols, age 81 (!)

Eddie Collins will depart in 1951, adding Mel Ott, age 42

Kid Nichols will depart in 1953, adding Ted Williams, age 35

Oscar Charleston will depart in 1954, adding Jimmie Foxx, age 47

Honus Wagner and Cy Young will depart in 1955, adding Stan Musial (35), Joe D (41)

1958: departing: Speaker, Ott, adding: Gehringer (55), Bullet Rogan (65)

1959: departing: Lajoie, adding: Spahn (38)

Ok, I'll stop here. Let's see who are the 12 greatest living ballplayers as of Jan 1, 1960:

- 75 Pop Lloyd

- 73 Ty Cobb

- 66 Bullet Rogan

- 63 Rogers Hornsby

- 59 Lefty Grove

- 56 Charlie Gehringer

- 53 Satchel Paige

- 52 Jimmie Foxx

- 45 Joe Dimaggio

- 41 Ted Williams

- 39 Stan Musial

- 38 Warren Spahn

And who are our (so far) 14 departed members:

- Christy Mathewson

- Lou Gehrig

- Walter Johnson

- Josh Gibson

- Babe Ruth

- Pete Alexander

- Eddie Collins

- Kid Nichols

- Oscar Charleston

- Cy Young

- Honus Wagner

- Tris Speaker

- Mel Ott

- Nap Lajoie